Refugee Trek

Sitting on her deck, overlooking the lake, she knows that the planes she sees are harmless, but the diving sound still strikes her emotionally, resurrecting one of her earliest memories: escaping Danzig and the advancing Soviet Army at the end of World War II.

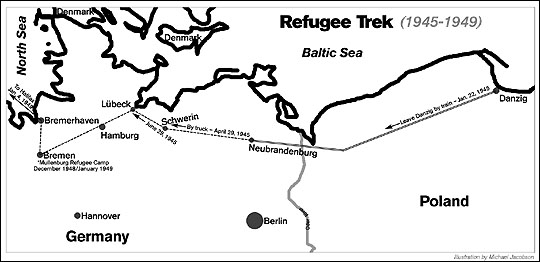

In 1945, at the end of World War II, with the German Army retreating from the Russian Front, Lorenz and her German family left their home in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) with little more than the clothes on their backs and began a four-year trek, which finally ended when her family emigrated to Canada in 1949.

In 1945, at the end of World War II, with the German Army retreating from the Russian Front, Lorenz and her German family left their home in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) with little more than the clothes on their backs and began a four-year trek, which finally ended when her family emigrated to Canada in 1949.

Lora with one of the few heirlooms that she possesses is this 18th Century Bible, used by her great-great-grandfather as a pastor in Berlin.

"My first recollection is going along the road with the dive bombers coming at us and being strafed and being thrown into a ditch," said Lorenz. "And the sky all ablaze and burning and the sound of the bombs."

Lorenz was born in 1941, midway through World War II, and remembers virtually nothing from Danzig, as her family fled the largely German city while she was still a toddler. Her older sister and her older brother, who was born just weeks before Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, remember more of Danzig.

The three siblings, along with their mother and grandmother, left Danzig and escaped the advancing Soviet Army and future Communist rule by a four-year refugee trek by train, truck, foot, and boat that eventually brought them to a new life on Canada's west coast.

Life Under Nazi Rule

A port city on the Baltic Sea, Danzig became part of Germany in 1793. By the end of World War I, in 1919, the city itself was 90 percent German, though the surrounding countryside was Polish. In the Treaty of Versailles following WWI, an independent Poland was formed, and Danzig became a free city, part of an international area between Poland, which needed a port on the Baltic, and East Prussia, which was separated from the rest of the country but was still part of Germany.

Lorenz's maternal grandparents owned a floral shop in Danzig, and her father worked as a banker.

Her grandfather, in 1937, got in trouble with the Nazi supporters. According to an oral history compiled by Lorenz and her two siblings, her grandfather was a Social Democrat (enough to put him at odds with the Nazi Party); made funeral wreaths for Communist funerals as well as Nazi funerals; and insisted on saying "Good morning" or "Good evening" as a greeting, not Heil Hitler.

Her grandfather, who fought for Germany in World War I, saw through Hitler and the Nazi Party, said Lorenz. Her grandfather knew that Hitler "was not what he seemed to be." He probably would have ended up in a concentration camp if he had not left for Canada in 1937, she added.

"He was advised that it would be better for his health if he left," said Lorenz. So he emigrated to Canada, where two of his children had already gone. But he always expected to return to Danzig. He expected to stay in Canada only until things settled down in Germany.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, starting World War II, within days, German troops entered Danzig. Two weeks later, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler himself visited Danzig.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, starting World War II, within days, German troops entered Danzig. Two weeks later, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler himself visited Danzig.

Lora Lorenz (bottom) escaped Danzg with her mother (top center) and two siblings. Her maternal grandmother also made the four-year trip with them to Canada.

Lorenz's father was drafted into the German Army, probably in 1943, and sent to the Eastern Front in Russia. When drafted, her father either had to fight in the army or put himself at odds with the Nazi authorities. He didn't want to go to war, said Lorenz, but he had little choice. Her father was in his late 30s with three little kids when drafted.

He was killed in February 1944 while serving with the retreating German forces in the Pripet Marshes, the largest swamp in Europe on the border of present-day Belarus and Ukraine. He was killed by a sniper and buried in the marshes. His commanding officer sent his wedding ring, his passport, his family pictures, and a picture of his grave to the family.

His family learned of his death three weeks later.

Refugee Trek

Eleven months later, Lorenz's mother was preparing to leave Danzig and take her family west.

Because of enmity between Germany and the Soviet Union, Germans in Danzig and Prussia feared the advancing Soviet Army. Refugees from the east told horror stories about treatment by Soviet troops, and Germans feared for their safety.

Her mother not only listened to German radio - which broadcast merely propaganda in which Germany was always winning the war - but to Radio Free Europe, an Allied broadcast intended to deliver real news to the European population. Her mother knew - from listening to Radio Free Europe in the bathroom with the faucets running at full blast so no one could hear her and report her to the authorities - that the German Army was retreating and the Soviets were advancing.

The family - mother, grandmother, and three kids - left Danzig on Jan. 22, 1945. They used two sleds to get to the train station but boarded the train with only what they could carry - a couple suitcases and backpacks. (It took some convincing to get her brother to abandon his sled at the train station.)

They squeezed onto the train, already overflowing with refugees, and headed to Neubrandenburg, a city about 100 miles north of Berlin where their great aunt lived. Normally, it took only eight hours by train to get to Neubrandenburg.

But these were not normal times.

It took them 72 hours, and they were lucky to make it. At one stop, her mother befriended a station attendant who secretly shepherded them away from the crowd of refugees and got them on a train headed west.

They stayed in Neubrandenburg for three months in the house of their great aunt. Some German soldiers also stayed in the house, and when the front lines pushed closer, they helped the family escape.

It became apparent that the German Army was still retreating and that the Soviet Army was still advancing from the sounds of the artillery guns, which kept getting closer and closer. They knew the Soviet Army was close when residents cut down oak trees throughout the town and used the logs on the roads to slow down the advancing Soviet tanks.

Lora Lorenz and her German family escaped Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) in 1945, avoiding the advancing Soviet Army. They traveled by train, truck, foot, and ship - living for over three years in an attic in Lubeck - before emigrating to Canada in 1949.

Lora Lorenz and her German family escaped Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) in 1945, avoiding the advancing Soviet Army. They traveled by train, truck, foot, and ship - living for over three years in an attic in Lubeck - before emigrating to Canada in 1949.

With the family desperate for transportation, the German soldiers who knew them linked hands and stretched out across a road to stop a German Army truck. Then an officer ordered some of the soldiers out of the truck and make them walk, making room for the Lorenz family to ride on the truck.

Her great aunt remained in Neubrandenburg, which became part of East Germany and came under Communist rule following World War II. "She stayed and was never heard of again (by the family)," said Lora.

Had her family stayed in Danzig - or been caught by Soviet troops (who would have sent them back to Danzig) - they, too, would have been trapped, behind what became the Iron Curtain in Communist-ruled Poland.

After escaping the Soviet Army, the family went next to Schwerin, where they stayed for two months. While they were in Schwerin, Germany surrendered (on May 7, 1945) and the Potsdam Conference - establishing the post-war spheres of control in Germany,╩dividing the country into four zones (American, British, French, and Soviet) - was held (for two weeks in July 1945).

After learning that Schwerin would probably become part of the Soviet-occupied section of Germany, which later became East Germany, the family moved again. This time, it was a short trip, a mere 30 miles to Lčbeck, just over the border in what became West Germany on June 29, 1945. "Mother was horrified that all her sacrifices and deprivation and difficulties might come to nothing, and we might still wind up under Communist rule," said Lorenz of this move. "She was determined that would not happen to us."

Life in Post-War Germany

Millions of German refugees moved west at the end of World War II, wanting to avoid the Soviets and viewing the western Allies as more humane. They all came to a war-destroyed West Germany.

According to Lorenz and her siblings, American troops could be very kind but unpredictable, French soldiers were vindictive, and British troops were best, extremely disciplined. After arriving in Lčbeck, a British soldier smuggled a message to their relatives in Canada, telling them they were alive.

In Lčbeck, the family first stayed in a single room with another family in a house owned by a German family whose husbands and sons were in the army. Then they moved to an attic in another house.

The attic, which was their home for three and a half years, measured roughly 10' by 30', though the usable area was less due to the sloping sides of the roof. Amenities in the attic were a potbelly stove for warmth and cooking and a bucket for nighttime bathroom needs. (Otherwise they had to use the trap door, go down a ladder, continue downstairs, and go outside to the outhouse.)

Lora started school in Lčbeck, where the schools were still being used as hospitals. (Her older siblings had attended school already and continued in Lčbeck.)

In post-war Germany, everything was scarce, especially food. During the first year, the family survived by eating turnips. They ate 1,300 pounds of turnips that year, cooked every which way (boiled, fried, and mashed). If they had any other vegetables, they mixed them with the turnips. The German boy living downstairs once came home with a whole head of cauliflower, which was a rare treat for all the people in the house.

Scarcity was so severe in Lčbeck that Lora's sister and mother shared a pair of shoes. Her sister would wear the shoes to school, and her mother would stay home. Then when they got home from school, her mother could use the shoes to run errands and go shopping, which consisted of standing in lines and hoping there were enough supplies for her family to get a little margarine or some sugar or flour.

Her mother - who was always positive, Lora said - earned income by sewing, using a hand-crank machine in the attic. Since new fabric was scarce, she used men's clothes, of which there was an abundance since so many German men had died in the war, and remade them into women's and children's clothing. Lora and siblings would help her mother and grandmother take apart the men's suits so her mother could sew new garments.

The family also would unravel socks, if they had holes, so mother could use the yarn to knit another pair.

As kids, they had few toys, said Lorenz. Most were improvised, like a stick and a rusty wheel. They also had to help the family survive by doing various chores and tasks.

Her family started receiving care packages from their relatives in Canada, including packs of cigarettes, hidden to avoid being stolen. They used the cigarettes to trade for food in Lčbeck.

Emigrating to Canada

Her mother decided to leave Germany because she saw no prospects for the family in the devastated country, said Lorenz. But she always told her children never to forget Germany and to always remember that their father fought on the German side during the war.

The family tried to emigrate to Canada in 1948, but her mother refused to deny her German citizenship and heritage. A quota existed for Germans emigrating to Canada, which they did not make, forcing them to wait until 1949, while as Poles from Gdansk (the Polish name for Danzig) they could have gone in 1948, as there was no immigration quota for Poles from Gdansk.

Before Christmas 1948, they went back to the refugee camp near Bremen and tried to emigrate to Canada again. This time, they were successful, and they left from Bremerhaven, bound for Halifax, on Jan. 4, 1949. Aboard a former troop transport, they arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax ten days later. Pier 21 is the Canadian equivalent of America's Ellis Island, the main immigration center for the country.

"Starting on the boat, we got food. We got good food," said Lorenz, who unfortunately suffered from seasickness on the trip and could not eat as much as she wanted.

After arriving in Halifax and undergoing health inspections, shots, and paperwork processing, they took a refugee train to Saskatchewan, near Prince Albert, where they stayed for three months with an aunt and uncle and their grandfather at their aunt's and uncle's chicken farm. (Her grandmother and grandfather were reunited, briefly, for the first time in 12 years, having last seen each other in 1937.)

Then Lora, her mother, her siblings, and her grandmother continued to Vancouver, where another uncle lived. After nine months with this uncle, they bought a rickety old house in Vancouver that became their first real "home" since leaving Danzig. "It," said Lora, "was ours."

Having relatives in Canada was a big help in their emigration from Germany, said Lorenz, who grew up in Vancouver.

Being German

Growing up, Lorenz hated history class when the topics were World War I and World War II, because the Germans, all Germans, were characterized as warmongers and blamed for the wars. The painful message was that all Germans were warlike, that all Germans were bad.

She was called a "Nazi" in school. And she believes her brother faced even rougher taunting.

What her tormentors did not know, though, was that her feelings toward the Nazis was even stronger than theirs. To her everlasting dismay, her birth certificate (in Nazi-controlled Danzig) is stamped with a swastika, a symbol she would like never to see again, though she realizes that the world needs to remember the horrors of the Nazis to avoid repeating them.

Today's history is better than it was when she went to school, Lorenz believes, because the context of what led to Hitler's ascent to power and to Nazi Germany - the unfair ending of World War I, the dismal economic situation of Germany in the 1920s, and the downtrodded attitudes of the German people ripe for a charismatic leader - are explained. While Hitler's evilness is now widely known, it was not obviously apparent in the 1930s, especially in Germany, noted Lorenz. Under Hitler, the German economy in the 1930s rebounded, and things like the autobahn system were started.

She still cringes, though, when war is portrayed gloriously, whether in history books, in films, etc. "As in any war, it's the innocent that suffer. It's the everyday people," she said, knowing from experience the affects of war.

Though neither a pacifist nor an anti-war activist, she abhors violence and rues the affects of war, especially on children.

"I don't see why we all can't get along on this itty, bitty planet," she said. "War is hell. No matter what side you are on," she added.

Lorenz - who moved to the United States in 1962, moved to Minnesota in 1976, and soon after became a U.S. Citizen - hates apathy, especially in voting. "That's how people who shouldn't be in power get in power," she said.

She considers voting a privilege and people should use it. "I still maintain that if you sent the generals to fight there'd be no war," said Lorenz, who retired in 1992 to Lake Koronis with her husband, Dale, a former college administrator. They have five sons and recently celebrated a grandson's return from military duty in Iraq.

If World War II had been avoided, or had it played out differently, Lorenz might have known her father. Instead, all she has of him are a few pictures - her mother remembered to bring one family photo album with them from Danzig - and stories told her by relatives.

In 1939, her father had a chance to take a job with his bank in Cairo, Egypt. But he refused the transfer because Lora's older brother had just been born. Had they gone, muses Lora, her father - along with the family - probably would have survived the war.

"Who knows how life would have been?" she asked. "Tiny things change lives.'

Contact the author at editor@paynesvillepress.com • Return to News Menu

Home | Marketplace | Community